The Case Against Work-Life Balance: Owning Your Future

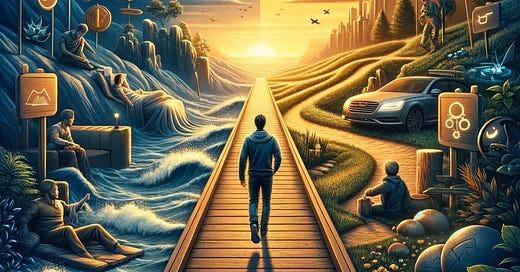

Chose life over balance to own your future.

Given my journey, you can imagine my first reaction to questions of work-life balance is fairly unsympathetic. I want to protest that, by legitimizing such a false dichotomy, you’re pre-empting a much more meaningful conversation. But I suspect that conversation is closer to the heart of this anxiety than most people realize.

If you’re worrying about work-life balance at the beginning of your career, and you’re reading this, I’m guessing you’re not lazy. You’re not looking for an easy life (even if this seems like an appealing concept right after midterms). I’m willing to bet that what you’re really worried about is someone else owning your most precious possession: your future.

Staring into the abyss of companies that glorify triple-digit hours (never mind the substance of the work), this makes intuitive sense. But having surveyed the landscape of high-tech hiring, I’m convinced you should be just as concerned about jobs that promise high stimulation and total comfort. When you let yourself be sold on easy hours, outrageous perks, and glib assurances about the project you’ll join and the technologies you’ll get to play with, you’ve just agreed to let your future become someone else’s.

I hate the construct of work-life balance for the same reason I love engineering: the reality is dynamic and generative, not zero-sum. It’s about transcending the constraints of simplistic calculations. Creating the life and the work you want are by no means easy challenges, but they are absolutely attainable. What’s not realistic is thinking you can own your future and be comfortable at the same time. Grit, not virtuosity, will be the biggest determinant of your success, for reasons I’ll explore in a bit.

At the same time, grit and discipline aren’t enough. You need purpose. And I can state categorically that the purpose you discover, with all the sacrifice that entails, will be more motivating and meaningful than the one handed to you in the form of some glamorous project that, realistically, will succeed or fail regardless of your involvement.

The catch, of course, is that true purpose doesn’t sit around waiting to be discovered. It requires constant pursuit. Here’s what I’ve learned from a decade and a half of sprinting.

There’s no time like now. As learning animals, we’re subject to various ages of cognitive potency. As a young child, your aptitude for acquiring a language or learning an instrument is at its peak. Accordingly, as a professional, your early 20s are the most formative stage. It is absolutely critical to make the most of this time because the pace of learning grows slower and more incremental as you age, whether we care to admit it or not. Of course, you can always learn new things, but most often the wisdom of experience is largely the result of earlier realizations having the time to compound into something richer.

The place of maximal learning is often at the point of significant pain. It’s not just about having a more pliable mind - grit, and its close cousin, resilience, are essential for taking your intelligence further than it can get on its own. And while intelligence compounds, grit degrades in the vast majority of cases. Regardless, grit isn’t something you can suddenly develop after a life of leisure. For these reasons, owning your future means choosing grit over the allure of a predictable pace.

Of course, you still need to hold a pace. Studies show that marathoners/endurance runners do tons of self-talk to push past the pain. “It’s a marathon, not a sprint” is a well-worn cliché, but it’s striking how often it’s invoked to rationalize comfort as opposed to promoting sustained excellence. Don’t think for a second that elite marathoners have trained to the point that a sub-six-minute mile pace is comfortable. It’s incredibly painful. What separates the truly elite is having found a purpose that makes the sacrifice acceptable.

At the same time, complete self-motivation is incredibly rare. It’s probably not a realistic goal, and that’s fine. Find the people who will sharpen your resolve as well as your ideas. Again, your first step matters. If you choose a job for work-life balance, chances are, so did everyone who came before. Talent is one thing when evaluating your future teammates, but ask yourself this: when you need models and inspiration to be more than you are, will you be able to find them? Where will your gamma radiation come from?

You can find your zen in stressful, chaotic times. In fact, I’d argue this is the norm, even the ideal, for 20-somethings. Some adrenaline is good for your performance. Not having time to waste requires you to focus on the essentials and develop an innate sense of direction. That way, when you do eventually get to let your mind wander, it will be in rewarding directions. These days, I build in calendar blocks for “brain space”. That wouldn’t have made sense 10 or even 5 years ago – not because I have more free time now, but because, early in your career, you learn much more by doing than reflecting. And this can be the difference between creating your future and receiving it in a fancy envelope.

At the limit, you probably should care about work-life balance – it’s not going to remain a static thing your whole life. But at the margin, as a new grad, you should focus on the most important problem. Find the thing that motivates you, work your ass off, learn as much as you can, and trust that today’s gains will compound well into the future – your future.

Working your ass off isn’t bleak – it’s quite the opposite. Provided there’s a purpose, sprinting at an unsustainable pace is an act of tremendous optimism. A mindset of premature retirement might sound rosy, but in truth it’s deeply cynical and extraordinarily insidious – much more so than being overpaid or overpraised, and much harder to correct.

But back to the concept of caring about work-life balance at the limit, how do you know where the limit is? Isn’t life fundamentally uncertain? Here’s what I’ve come to realize: you can’t pre-emptively retire without doing the work that makes you appreciate the chance to rest. Maybe you can, but assuming you have something to contribute, it’s going to be an empty reward. Sacrificing your potential to comfort isn’t a hedge against an early death – it IS an early death. As Emerson wrote in Self-Reliance, "Life only avails, not the having lived. Power ceases in the instant of repose; it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of the gulf, in the darting to an aim.”

We’ve been told over and over to choose life over work in order to achieve balance. I’m urging you, especially at the dawn of your career, to instead choose life over balance, and make the work so meaningful that you wouldn’t want it to exist as a distinct concept. This is how you ensure that your future remains yours.