I’ve been thinking a lot about

’s interview with Paul Buchheit in . Paul, of course, is the creator of Gmail, one of the most revolutionary software applications of all time. Gmail has more than a billion active users—which means roughly one in seven people walking around today is using his product. That’s success, on a power-law scale.It only happened because Google empowered him to build it. They knew he was interested in webmail, so they told him to build an email application. They had raw talent on their hands, so they used it.

It wasn’t always pretty. As Paul describes, he butted heads with people internally along the way. Google didn’t use Javascript; he used Javascript extensively. And the Gmail launch was a PR disaster. Google was building the plane as they flew it. But that itself is evidence of innovation. A company that can tolerate disagreements, setbacks, and embarrassments is a company that can adapt and built world-changing products.

It’s hard to imagine any of the big tech companies allowing its young engineers to launch a work in progress like that today—much less something as consequential as an email service. And that’s exactly the problem. It’s also hard to imagine any of those companies building the next Gmail today, period.

Case in point: Google engineers gave us the transformer deep-learning architecture that’s powering the generative AI revolution… Yet Google’s AI applications aren’t grabbing headlines. Mostly they’re the punchline.

So what happened?

Paul suggests that Google succumbed to the common fate of bureaucracies over time: it stopped being an insurgent obsessed with innovation and started being a gatekeeper obsessed with preserving its status, image, and incumbency. This change didn’t happen overnight. It was a gradual process of entropy and attrition.

Companies like Google start out as ‘insurgents’ looking to make a name for themselves and dethrone Goliath-like incumbents (the IBMs of yesterday… the Googles of today). So they move fast, make bold pronouncements, and gamble furiously. Almost always, they have a founder who is laser-focused on the mission. And they attract lean, hungry insurgent types to work for them. People like Paul who are driven by the organization’s mission and vibe with its ethos.

Then these companies succeed. Before long, they look up and realize they’ve become the Goliath-like incumbent. Along the way, they’ve accumulated—in an effort to minimize friction, fighting, and chaos—a million different rules and procedures and barnacles that slow the organization down and make the kind of innovation they were known for in the beginning impossible. Often they’ve driven out the very insurgents who got them to the top, because at some point their prickliness and risk-taking began to be viewed as threats to the business rather than precious resources to be hoarded.

The fundamental change in mindset between insurgency and gatekeeping is that the organization’s tolerance for risk, messiness, and adaptation goes down. The understandable, human desire for predictability, control, and safety—the rallying cry of gatekeepers from Silicon Valley to Washington—stifles genius and innovation, qualities that are unpredictable and uncontrollable by their very nature.

Paul described the gatekeeper mindset as follows:

said as much, as well.Gatekeepers are one hundred percent anchored to stopping bad things from happening, and they have no concept that when you stop bad things from happening, you are inherently stopping good things from happening as well. You can't ever deliver something that's 100 percent good. If you deliver 80 percent good, that's pretty good. But if you try to go for 100% — if you try to be perfect — what you get is nothing. Innovation is inherently not clean.

Once you see this insight, you start to see it everywhere, from the macro level on down.

Countries and entire civilizations can be viewed as gatekeepers or insurgents, though usually they’re a mix of the two.

The United States was an insurgent, a startup nation forged in rebellion against the Old World, whose trade and diplomacy were quite obvious forms of gatekeeping to preserve the privileges of incumbency. It was the insurgent spirit that led Americans to go West, launch men into the sky, and ultimately land them on the Moon.

Now we look up in the year 2024 and we’re the incumbent—which is a great thing to be, provided we can keep our edge. But that’s not a given. Already we can see the gatekeeping mindset creeping in, from the EV chargers we’re failing to build to the astronauts we just stranded on the International Space Station. (It might take a genuinely insurgent organization, SpaceX, to get them down again.)

Zooming in, we can see the “gatekeeper vs. insurgent” battle closer to home—including in our own organizations and careers. When reading Solana’s piece, I recalled times when I have found myself turn into a gatekeeper and what I had to do to reclaim my revolutionary zeal. The forces of entropy and attrition that corrupt companies do the same to humans.

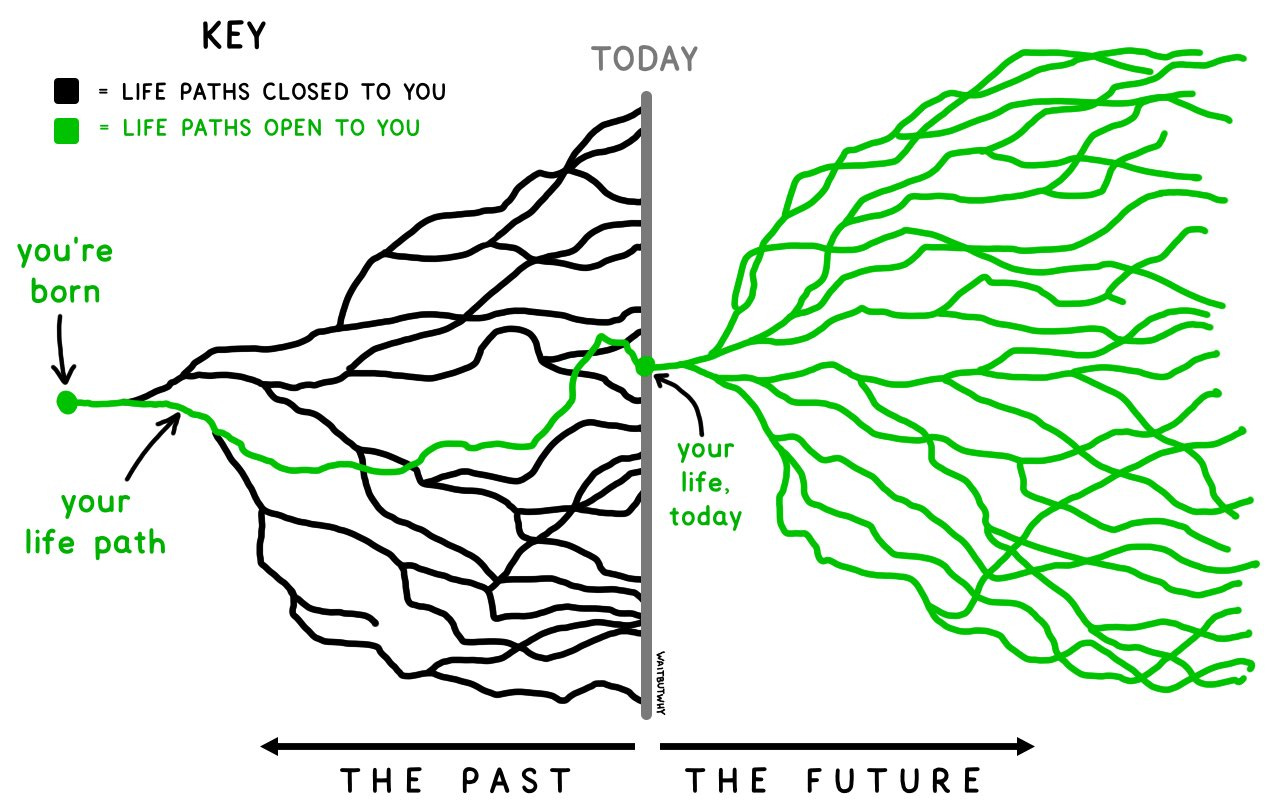

I’ve written before about the illusion of the “career ladder.” People have been trained to think that their career proceeds linearly, rung by rung, in a stable and predictable path upward. It’s an attractive illusion, promising stability and security. This year you manage a team of four. Next year, it’ll be a team of eight. The next rung will always be there, safely within your grasp.

But it’s an illusion all the same.

Once you embrace the concept of the ladder, you constrain the many pathways available to your future self down to the single, planned, predictable pathway ascribed by your employer. You are blinded to avenues outside of the ladder. And you will likely start to pick up other bad habits of bureaucratic organizations, like mistaking your title, total compensation, or the head count of employees that you manage for your effectiveness. Or obsessing about safety, compliance, and stopping the bad instead of facilitating the good.

By a slow and subtle process, your mind has been fenced in by the gatekeepers. You have been gate-kept. And you are being assimilated, Borg-like, into the ranks of the gatekeepers.

The truth is that the most brilliant and meaningful careers proceed in fits, starts, zigs, zags, and lateral plays. Your life isn’t about climbing a ladder. It’s about swinging from vines, Tarzan-style.

So knock over the ladder and grab hold of a vine.

Alex Karp likes to say that the best business movie ever made is the 36th Chamber of Shaolin, because it teaches that even once you’ve fought your way to the top and reached the “culminating” point in your career—by becoming CEO, say—there’s always the 36th chamber: the one you have to invent yourself.

(Spoiler Alert): When you reach the final chamber recognized by the orthodoxy—the 35th chamber—you realize only way forward is to go full-on insurgent, invent a new chamber, and democratize Kung Fu for the people. It’s precisely at those moments when you need to examine your motivations and change the game if you’re starting to act like a gatekeeper instead of an insurgent. Insurgency is the pinnacle chamber.

This applies especially to those of us who have the dubious honor of being managers of other people. Precisely because of our position, we have the ability to empower our best employees—or to stifle them like a wet blanket. With great power, comes great responsibility.

I remember when Palantir was just starting our commercial business. We hired two very special engineers. They were the definition of insurgents: 100x talents with a hunger to build. They were raw and difficult and abrasive. But they were brilliant.

I thought it was my job to manage them and smooth their rough edges. But to dull their deficiencies was to dull their superpowers. Eventually I realized I was destroying value. I might prevent a bad idea now and then—but for every one bad idea, I was preventing five interesting ones from seeing the light of day. I was becoming a gatekeeper.

What I really needed to be was a janitor. Sure, I needed to expose them to the gamma rays that raw talent needs to grow into greatness. But really I needed to clean up the messes that insurgents inevitably leave in their value-creating wake, like the Incredible Hulk.

And I’ve seen this pattern repeat in those below me. It is a natural process—the entropy of the universe. The only question is whether that person can come to terms with the need to reinvent themselves as an insurgent or prefers to gatekeep themselves and others. That reinvention is always incredibly painful and dislocating.

So what does it take to reincarnate as an insurgent, when human nature pulls us in the opposite direction?

First, make sure you are a leader that doesn’t say “forward,” but “follow me!” Structurally, you can’t be an insurgent if you aren’t in the details and leading from the front. I’ve committed myself to always attaching to a set of projects I’m personally going to drive forward (as an IC). And this is what I’ve seen successfully transform gatekeepers into insurgents around me. So burn the boats and devote all your time and energy to driving the most important projects forward.

Second, make sure you have an incredibly talented, incredibly independent team that’s focused on the Primacy of Winning. Employees who need, and demand, the freedom to experiment, call audibles, and challenge you whenever you’re wrong. Who resist the gatekeeper forces in themselves and others. I like to say that Palantir is an artist colony, and I chose the metaphor advisedly. Van Gogh was not an easy guy to work with. But he minted masterpieces.

Above all, insurgency requires soul-searching, self-criticism, and honesty about our own motivations. Man isn’t born a gatekeeper or an insurgent. We become these things through our actions.

What path will we choose today?

I say: Viva La Revolución!

Company leaders across all industries should embrace this spirit of "¡Viva la Revolución!". Hope they consider discussing this concept in board meetings and company-wide gatherings to inspire employees and stakeholders to embrace change and drive progress.

Shyam, I am new to your blog, this being my first story to ingest. What drew me to Palantir was its ability to be a bureaucracy buster. AIP is a benevolent and transparent Trojan Horse. It is the ultimate insurgent that corporations welcome to cure themselves of gatekeeperitus. I promise, as an observer, to let you know if your sword dulls, or your courage wains. Thank you for welcoming me to your group. This is awesome!